In the creation of this post I am indebted to the meticulous work of the late Ian Brand F.C.I.S. and his book, Escape From Port Arthur. Thanks are also due to my dear friend, Peter O’Donnell, who found this story for me, and to David Roe of the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority.

In 1839, in the very early days of the penal settlement at Port Arthur, eight men contrived an escape. It led to an almost inconceivable journey: a thousand miles, past some of the world’s most forbidding coastlines, all in an open whale boat.

This is a story that has not often been told. In Escape From Port Arthur, Tasmanian historian Ian Brand drew on original documents to record it in as much detail as he could. He said:

This journey must rank as one of the greatest in Australia’s early history.” (p. vii)

Mysteries

A story like this leaves us with many questions. The eight men, after years as convicts, had experienced hard labour on chain gangs and been punished with the lash. In their determination to escape they exposed themselves to extremes of cold, hunger and mortal danger for weeks on end. What must it have been like for them, day by day, surviving at sea, moving up and down inhospitable coastlines in an open boat, scavenging food and clothing when they could? Maybe it is surprising that, despite these hardships, they worked hard to avoid violence and, by all accounts, conducted themselves with decency and civility to everyone they encountered.

Ian Brand pieced together the men’s movements and their encounters with settlers and authorities from convict records and reports.

And yet raw documents, while containing much character in their own right, naturally fail to flesh out the personalities of the men involved and the more intimate details of their extraordinary journey. If we want to understand the immediacy of their experiences, we must use our imagination. But here is their story.

Port Arthur

Port Arthur was established around 1830, firstly as a timber cutting settlement and soon after as a place of secondary punishment for convicts who had committed serious offences while in Van Diemen’s Land. From its earliest days it was both criticised as harsh and praised for being well run (Alexander, 2010).

In those earliest days, the site was different from the way it appears today. Many of the stone buildings had not been built and the extensive land reclamations had not been done.

The site was chosen for a penal settlement partly because of its remoteness and security. It was surrounded by dense and uncharted bush and the southern ocean. Few convicts could swim. The Tasman Peninsula is connected to the Forestier Peninsula by a narrow neck of land at Eagle Hawk Neck which was watched by guards and dogs, and another neck connects this to mainland Tasmania.

Despite this, throughout the convict period (1830 – 1877), there were frequent efforts to escape.

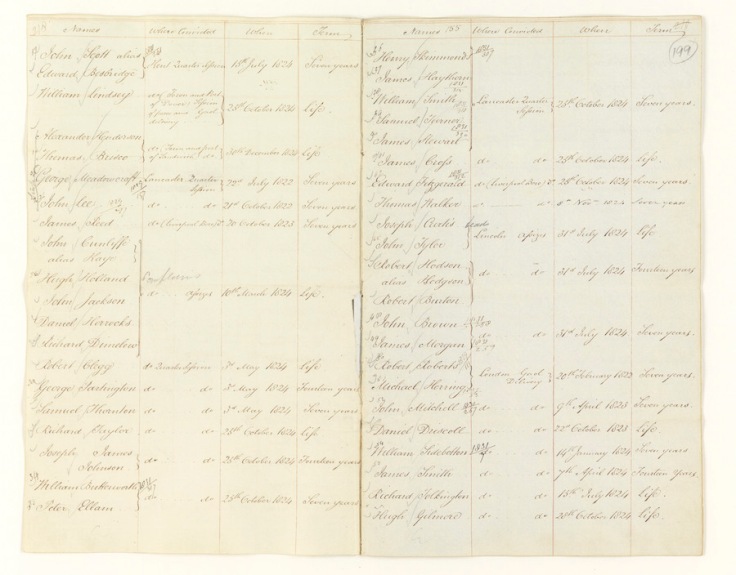

The escape of 1839 was undertaken by eight convicts, all originally sentenced to transportation for stealing and housebreaking offences. Rebellious and insubordinate, and often violent in their past lives, these men had spent time in chain gangs, road parties and penal settlements. Many had received lashes as punishment, some on several occasions.

All had recorded previous attempts to escape.

Thomas Walker

The natural leader of the group was Thomas Walker. He was reported in convict records to be five feet nine inches tall with brown hair and light grey eyes.

Walker had been sentenced in 1824, for stealing a handkerchief and money during a housebreak. He had arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1825 and since that time had been charged with neglect of duty, absence without leave and disobedience, and also of stealing.

He was a very experienced escaper. He had escaped from the chain-gang at Bridgewater (twice), the Hulk chain-gang, the Grass Tree Hill chain-gang and from a previous stretch in the gaol in Port Arthur. On occasion, he had hidden himself in barques, hoping to be taken to sea.

On recapture, Walker was customarily punished with lashes. He had received fifty lashes on one occasion, on others 100, and even 150. In all, over his life he had felt a total of 1006 (Brand).

Walker was perhaps the natural leader of the group, but many of the others were also experienced escapers and they must have all been not only hardy, but very determined.

The Collaborators

They were:

John Thomas, 28, 5ft 1½ inches tall;

James Woolf, alias Mordecai, sentenced aged sixteen, now 26, with a “proud visage” and dark hair and brown eyes;

George Moss, 29, sentenced for stealing a watch and a purse, with only minor offences recorded since arriving;

Henry Dixon, sentenced to hang for stealing a ferry boat with the sentence commuted to life imprisonment;

John Jones, 4ft 11 in tall, sentenced aged 12 for stealing, now aged 25;

Nicholas Lewis, or Nicholas Head, or Michael Head, a sailor with a sallow complexion, recently back from the coal mines on the north of the Peninsula

and James County, 29, like the others an experienced escaper and with much experience of chain gangs.

Obstacles to Escape

At Port Arthur in 1839 the prisoners were housed in a penitentiary, consisting of a collection of wooden huts around a series of yards, on the southern shore of the bay. The outer fence was patrolled by watchmen night and day.

“The men sleep singly, as a lamp is kept burning all night, the least movement can be observed by overseers at the end of the room.”

(Thomas J. Lempriere, Commissariat Officer, 1839, in a piece titled “Penal Settlements of Van Diemen’s Land”, reproduced by the Royal Society of Tasmania 1954.)

Another obstacle was the possibility that escape plans would be reported to authorities. In penal settlements there were rewards and leniencies awarded to informers (Alexander, 2010).

Nevertheless the eight men managed to communicate sufficiently to arrange an escape. They were all engaged on the settlement’s boat crews. Six of them were crew of the Commandant’s 6-oared whale boat and two were in the crew of the No 3 whale boat.

It is possible that there was not a lot of elaborate planning required. Their plan was simple.

They resolved to snatch a boat.

In Port Arthur at that time the wooden boat shed and Commissariat store were situated near the Military Barracks, directly beneath a guard tower, and under the direct surveillance of an armed sentry.

Whenever a boat was taken out, an armed guard travelled with prisoners.

With escape at night from the penitentiary almost impossible, and the seizure of a boat containing an armed sentry also unlikely to succeed, the men resolved simply to run to the boats during daylight, seize one, and row for their lives.

Cool and Deliberate

Some days before the escape, Captain O’Hara Booth, Commandant of Port Arthur, had been informed of a plot to escape and had tightened security over the boats.

Booth had himself been “more than usually vigilant” and had taken what he considered to be sufficient precautions to prevent it (from Booth’s report to the Governor, via the Colonial Secretary, quoted in Brand).

The precautions were to prove inadequate.

On the morning of 13th February, 1839, taking advantage of a “momentary absence” of the sentry, in broad daylight and in a “cool and deliberate manner”, Walker and his men launched the Commandant’s Whale Boat from its slip and rowed straight out through the heads at Port Arthur. Then they simply kept going, southwards, directly out to sea (Booth’s report).

As soon as the theft was noticed, the Commandant took five men in a second whale boat and they pursued the escapers for five hours. About thirty miles off-shore, in thick haze and out of sight of land, they lost sight of them.

Part II coming soon.

References and Further Reading

Alexander, Alison (2010), Tasmania’s Convicts: How Felons Built a Free Society. Crow’s Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Brand, Ian (1991), Escape from Port Arthur. Launceston: Regal Publications.

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish and Hood, Susan (2001), Pack of Thieves?: 52 Port Arthur Lives. Port Arthur, Tas. : Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority.

http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/P/Port%20Arthur.htm

Leave a comment